A History Lesson: Appreciating the Role of the American Teacher

By Gary Funk

"The windows were five in number, of twelve panes each. They were situated so low in the walls as to give full opportunity to the pupils to see every traveler as he passed; and to be easily seen."

A teacher, whose name is long forgotten, describes an 1810 New England school.[i]

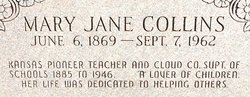

Jane Collins was born in Nemaha County, Nebraska in 1869. Her father was a jack of all trades—a farmer, dairyman, and dentist. Jane’s mother’s name was Minerva, and she had five brothers and sisters. In 1874, Jane’s father moved the family to a farm near the town of Simpson in Cloud County, Kansas. This is where Jane and her siblings grew up. This is where she attended her first school classes in a dugout schoolroom.

Like scores of other young women across the prairie, Jane developed a strong desire to become a teacher. Unlike some young ladies, though, Jane had a father who championed education and the rights of women. Her father’s encouragement and her personal ambition would lead to a remarkable career, a career that would include a superintendency and extraordinary community leadership and service.

Jane Collins began teaching when she was sixteen years old. She had to pass an examination and was issued a county certificate by the Superintendent of Schools of Cloud County. Her first contract was for a four month term, for which she was paid $30 a month. She boarded with a neighbor where she cooked meals, dressed the children, and helped milk the cows. The year was 1885.

Ms. Collins went on to teach for three more decades. She encountered some of the same problems teachers often face today. One year she had 50 pupils in her classroom; another year the desks were rough and homemade and would not adjust to the children. There were playgrounds with no equipment, and there were board members whose actions and comments were perplexing at best. After her retirement Collins recalled with humor a conversation she had with a board member during an interview for a teaching position. When she questioned the board member about the quality of the school’s equipment, the board member thought carefully for a few minutes and then “assured her that the district had a ‘right good stove.’”[ii]

After thirty years of teaching “Miss Jane” was elected Superintendent of Schools for Cloud County, a position she would hold for twenty years. She was a dedicated superintendent, and she was appreciated for her regular school visits, personal encouragement to students and teachers, and her penchant for providing clothes and food to families with children in need. In February of 1919 a county newspaper provided its readers with the following account:

“The W.P. Duvall family residing 12 miles from Concordia knows that there is at least one Good Samaritan in Concordia. That Samaritan is Miss Jane Collins, County Superintendent; and her merit to the title is this: When the roads were so icy Wednesday that liverymen refused to make the trip, and members of the family were too ill to come town for medicine, Miss Collins walked the twelve miles to deliver the medicine. She not only walked out, but walked part of the way back.”[iii]

In 1929, Miss Collins had to resign as County Superintendent due to illness, but she returned to the school house to teach three more years before she was again elected to the office of County Superintendent. She remained in that position until 1940 when she retired at the age of 71. The retirement was short-lived, though, and Miss Collins returned to the classroom in 1942 due to a severe teacher shortage brought on by World War II. She continued teaching until 1946, and, finally, at the age of 77, she retired for good.

What inspired such sacrifice and commitment? Why would a 73 year old woman give up her gardening, reading, crossword puzzles, radio listening, and violin playing to return to the daily grind of teaching young children? Perhaps it was the devotion of former students. Perhaps it was the admiration of her peers. Perhaps it was a family upbringing where women’s rights and public education were championed. Perhaps, just perhaps, it was nearly six decades of educational experiences that were grounded in community, a grounding where responsibility and personal satisfaction went hand in hand.

In 1954 Concordia, Kansas’ local Delta Kappa Gamma chapter, a teachers’ service sorority, prepared an article for submission to the Delta Kappa Gamma national publication, which was dedicating an issue to pioneer teachers of the United States. The tribute included these words:

“Miss Collins was a remarkable person. As an educator she was efficient, resourceful, and progressive, and as a neighbor she proved to be consistently helpful and understanding, a true friend to many who knew her. Her concern for the children she taught extended beyond the school room to include their life circumstances and those of their families as well. It was truthfully said of her: ‘She went about doing good.’”[iv]

Honoring Miss Collins

Some would defend America’s pendulum-like swing to the urban, the consolidated, and the centralized as a necessary dialectical shift from what were perceived as entrenched rural problems of poverty, inadequate opportunities, parochial prejudice, racial segregation, and a lack of public services. Certainly, these thorny issues were counterbalances to what was good and right in rural America. And without the rural to urban transition that followed World War II, some issues might have been more difficult to address on the national level. But the characteristic strengths of rural communities were carelessly discarded, and after a full century of American urbanization and coporatization, racism, limited access to health care, and other social injustices still exist. In fact, Jonathan Kozol contended in 2007 that our mostly urban and suburban public schools were more segregated than at any time during the modern era.[v] Knowing all this, we must ask, “Have our urban and materialistic gains outweighed our loss of community and purpose?”

A necessary rebalancing requires that with a Joshua-like fervor rural communities must bring down the walls that alienate school from community. The teaching of children should be transparent, a school without walls, without boundaries, where the pupils see and are easily seen. Yes, a room with many windows. Surely it is time to take what we have gained in technological capabilities and try to recapture the community values we have lost. Reestablishing a rural school model where students, teachers, and parents work together to do "good" in a place that has shared meaning—truly an American opportunity.

[i] Johansen, John H., Collins, Harold W., and Johnson, James A. American Education: An Introduction to Teaching. 1990, Dubuque, Iowa, William C. Brown Publishing Company, p. 237.

[ii] During my second year as a fifth grade teacher in rural Bolivar, Missouri a school board member said on the record that he wanted “his teachers to be like the buses—clean and shiny.”This was in 1981.

[iii] Freeman, Rosemary. “Jane Collins: Pioneer Teacher of Cloud County, Kansas, paper prepared for the local Delta Kappa Gamma committee and submitted to the Kansas One Room Schoolhouse Project, Southwestern College, Winfield, Kansas, 1997.

[iv] Ibid

[v] Kozol, Jonathon. “The Widening Gap,” speech made to the Missouri State University Public Affairs Conference on April 20, 2007.