Editor's Note: Parts of the story below were excerpted from the Community Foundation of the Ozarks' book, "Passion and Purpose." To listen to a podcast conversation between Arthur Mallory and the Rural Schools Collaborative's Gary Funk, go to Ozarks Public Radio, KSMU, and listen to "Stories of Hope and Help."

Arthur Mallory’s fingerprints are on so many important Missouri initiatives it is nearly impossible to keep track. A teacher, public school leader, Missouri State University president, and former Missouri Commissioner of Education, Mallory has shepherded important initiatives including school testing reform, special education legislation, the launch of Parents as Teachers, and the development of the Association of Retarded Citizens. Along the way he has encouraged and mentored scores of young educators as they moved up through the ranks, sharing with them his political savvy and commitment to community.

Mallory’s interest in education was certainly grounded in his own career, but his penchant for “thinking otherwise” about schools and communities had deeper family roots. To understand Arthur Mallory’s passion for education is to know about his father, Dillard.

Celebrating the Iconoclast

Dillard A. Mallory’s commitment to education was forged on a Verona farm with eight brothers and sisters. Born in 1907, Dillard initially attended a one-room school, and then with his three brothers, enrolled in the nearest high school, 10 miles away. They rented a small room near the high school, lived on pork and beans, and Dillard taught grade school to help pay their way. After graduating from high school, Dillard went on to be a teacher, administrator, and, finally, in 1944, the superintendent of schools in rural Buffalo. Life in Buffalo and surrounding Dallas County has always been hardscrabble, and building and maintaining a quality school district was a challenge. Fortunately for the community, Dillard Mallory was not deterred by traditional constraints or economic want.

In 1947, the Buffalo school district was on shaky financial ground and had many capital needs. Dillard decided to use $10,000 from his 20 years of personal savings to purchase a one-acre lot adjacent to the high school. He then leased it to the school district for $1 a year. Next, on his signature alone, he borrowed $32,000 from a local bank and bought surplus Army barracks, which he converted into a library, cafeteria, and home economics classroom. Mallory used money from athletics concessions and the cafeteria to pay off the debt, and he borrowed again to construct a science and industrial arts building. The lumber for this project came from an abandoned Army hospital. This all occurred over a 10-year span, a period during which Mallory turned down numerous positions in more glamorous communities. He stayed in Buffalo, remarking, “I had an idea that you could work out as good a program for children here as anywhere else.”

Mallory wasn’t finished. In 1957 he built a $72,000 “teacherage” with apartments for the district’s teachers. This addressed a housing shortage, and the $60 monthly rent was very attractive to young teachers. By 1959, Buffalo had reduced its teacher turnover, garnered a top-drawer “Triple-A” rating from the state Department of Education, and won overwhelmingly favorable votes to issue bonds for high-school renovations and raise the local school levy by 20 percent! During this same period, nearly 50 tiny rural districts petitioned to become part of the now-unified Dallas County school district, a remarkable vote of confidence in Dillard Mallory’s leadership.

Mallory received national recognition in the early 1960s for his innovative work, and he used proceeds from speaking engagements to establish a local scholarship fund for youngsters striving to become American Government teachers — a fund still in existence today for the Dallas County Community Foundation. Interviewed in 1963 by Time magazine, Mallory sensed that he may have been a remnant of an entrepreneurial era in public education. When asked what American public education needed, he told Time: “We've got to get back to greater effort on the part of the individual.”

Dillard Mallory was no soothsayer, but his comment on individuality seemed to anticipate an era when decision making and personal action would be de-valued. In a landscape as diverse as rural America, with its varied economic challenges, prescriptive top-down approaches to rural school reform often bring frustration. Stronger rural schools must have capable leaders and teachers who can think on their feet and act accordingly. Furthermore, school decisions should be rooted in place and involve local people.

Arthur Mallory’s own observations echoed his father’s realizations, and he recalled the time when civic and business leaders were more engaged in the school decision-making process. Mallory remembered how in the 1970s, during his first few years as Missouri’s Commissioner of Education, he could drive into a small town and quickly surmise who might be on the local school board. “All I had to do was drive down Main Street and look at the names on the signs of the hardware store, drug store, or car dealership. Almost without fail, one or more of those names represented a school board member. That certainly isn’t the case anymore.” Arthur Mallory’s recollection makes an astute point: purposeful efforts must be made to bring the business, civic, and education sectors together in meaningful ways. A high level of collaboration not only helps struggling school districts that often suffer from high rates of leadership turnover, but it also keeps public education at the forefront of local economic development.

Many other Mallory recollections are instructive. He once lamented, "One of our great educational losses happened when we stopped asking the older students to take care of the younger students." Obviously, this speaks to the varied roles and responsibilities that students once had in rural schools, but there is so much more to infer. Mallory's remembrance speaks to the loss of student ownership in the schooling process. It speaks to the loss of husbandry--the denigration of hands-on work. It speaks to the loss of community.

The Lesson

Arthur Mallory's storytelling is purposeful. He is not didactic; he is not preachy. Those who have been around him long enough realize that when he starts to talk about his "Daddy," you should pay careful attention. That is about as close as he gets to giving personal advice. To listen thoughtfully to Arthur is to take advantage of an opportunity to reflect on almost a century's worth of teaching, leadership and reflection--two generations combined. It is, essentially, a chance to find wisdom, a characteristic that has been discarded carelessly by a society with a penchant for lurching forward--often in an impatient and careless manner.

This unfortunate scenario is not so much about losing wisdom as it is not using it. It is particularly troublesome for our rural communities, as wisdom is one thing that cannot be outsourced, consolidated, or crammed into a box store. The elders are there. The stories are there, and so are the places. Wisdom has the power to bind, the power to educate, and the power to lead. It is a virtue, and it should be and is one of rural America's greatest assets.

Let's put it to use.

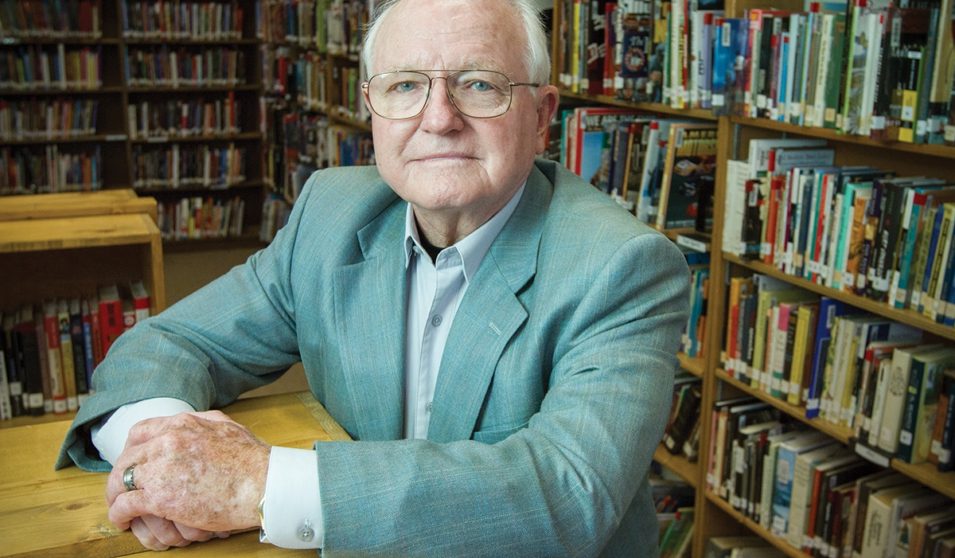

Below: Left to right: Mike Smith, KSMU producer; Gary Funk, and Arthur Mallory.