Exposing K12 students to the power and potential of the education career at a younger age is essential for strengthening the rural teacher workforce and rural communities. We reflect on the need for early rural teacher pathways at the middle and high school level through interviews with three great examples of these programs in the Rural Schools Collaborative network.

A thriving local school system is essential for the wellbeing and prosperity of rural communities. Not only are vibrant schools responsible for nurturing equally vibrant societies, but a strong school system also has the capacity to become a local economic development driver. Yet, these districts tend to be enduring some of the toughest challenges, including a persistent educator shortage. Thankfully, much is being done already to inspire, train, and place visionary teacher-leaders committed to utilizing both community assets and challenges alike for student and community success. Rural Schools Collaborative endorses the intentional recruitment, preparation, and retention of rural educators, called a Rural Teacher Corps, for this very reason. Rural teacher pathways provide aspiring teachers with the skills, mindsets, and human networks necessary to thrive in a rural school.

As these intentionally rural-focused teacher pathways have grown and matured, conversation among the burgeoning national network of Rural Teacher Corps partners has returned time and again to the need of building these pathways out to reach younger students. Historically, middle and high schools across the country often sported a Future Teachers of America chapter, or a similar variant, to offer early insights and know-how into being a classroom teacher. As both perceptions and interest in the education profession have waned however, these early touchpoints into the teaching career have steadily dwindled. In more recent years, efforts like Educators Rising and Grow Your Own have taken up the banner of inspiring kids to become teachers.

Today, the need for rural educators is as strong as ever, and many institutions are already leading the way forward in rural teacher preparation by hosting their own early pathways programs. We’ll explore three of these early pathways programs representing three distinct regions of the country: the Wisconsin Driftless Region, Eastern Oregon, and the Alabama Black Belt. While they serve widely different people and places, a set of common elements grounds the success of these efforts, and offers insights for the further enrichment of the concept. Some of these common elements include a focus on holistic student success rather than strictly teacher recruitment, using a collaborative model for program growth, and relying on adaptation and flexibility to create a localized approach. Understanding these programs more fully is imperative as we strive to collectively bolster the education profession so that rural students, schools, and communities may all benefit.

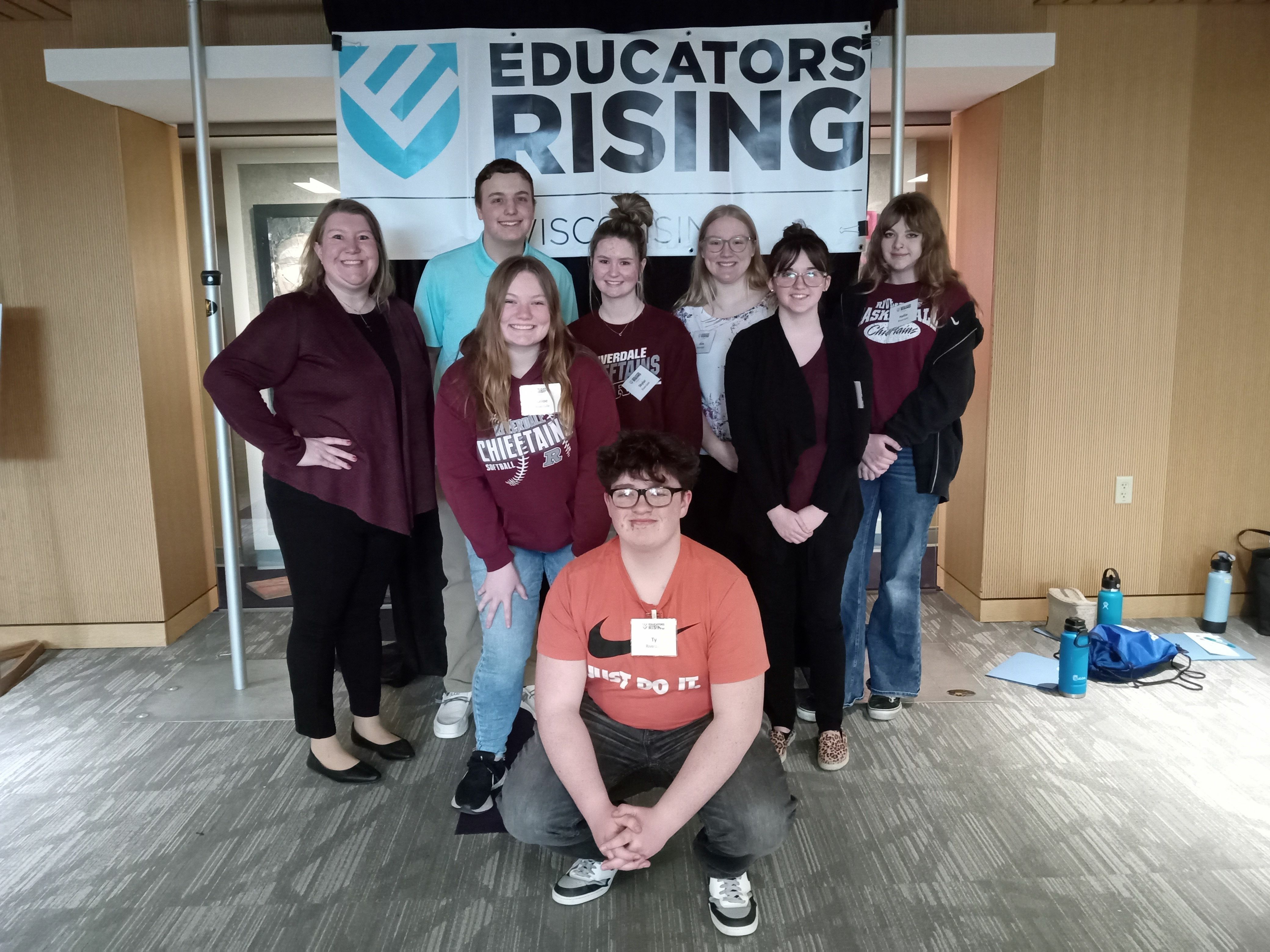

The Power of Partnerships in the Wisconsin Driftless Region

Resting along the banks of the Wisconsin River, Riverdale High School in tiny Muscoda, WI is home to an innovative teacher pathway program with national implications for how it incorporates regional collaboration and positive messaging about education. Sarah Ploeckelman is the Spanish teacher for the district in addition to being the coordinator for the district’s education pathways program. As a third generation educator, she has a deep respect for the profession, but soberly recognizes the challenges of sustaining a vibrant rural teacher workforce: “There’s not as much access to resources as a community here, and then of course that’s reflected in the school district. Enrollment is declining and unfortunately for many rural and small schools the first thought is to cut staff. But, that’s really backwards thinking. Instead, how can we be creative with the resources that we do have?”

Sarah and her district’s response was to channel both creativity and challenges into launching a pathway program that inspired local students to see themselves as educators, earn early college credits, and consider returning to support their home school. For two years now, Sarah has taught “Introduction to Education” to juniors and seniors in partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Platteville School of Education (UWP). By the end of the course, students earn two credits that are transferable to any of the 13 universities in the University of Wisconsin system. In addition to helping students gain insight into the teaching career, Sarah underscores that “it helps students get a start on their college education and save money because the school districts will pay for the credits as they attend the program.”

Although the dual-credit model is nothing new, Sarah shares that what makes her program unique is that, through the partnership with UWP, eight other small, rural schools in the area are able to collaborate with Riverdale to create a regional teacher pathway cohort. This arrangement is particularly powerful for rural schools. It is often difficult to justify the addition of a new program when overall student numbers to attend that new effort are low, especially so for education. However, by working together to pool both resources and students, districts can offer a more robust program with the added benefit of generating local networking and resilience.

Starting with just 9 students in 4 schools in the first year of operations, Sarah has grown the program to include 17 students across 9 districts. Part of what has helped the program grow is that, in addition to teaching, Sarah is the district’s College and Career Readiness coordinator. In Wisconsin, school districts are required to implement academic and career planning with students. Much like more traditional business and technical pathways, Sarah worked through this coordinator role to create the education pathway in her district’s academic and career planning. When she counseled students on their future prospects, education was now on the list of viable pathways to follow.

Along with the dual-credit program, Sarah shares that her district is trying out other approaches to expose students to the education field, including a future teacher club facilitated by Educators Rising and an apprenticeship approach that allows students to learn early childcare. Both of these other options open education opportunities beyond becoming a classroom teacher, such as school administration, childcare, and counseling.

Strengthening the teaching profession is necessary in its own right. However, Sarah stresses that establishing more pathways, like education, is also an act of service and equity for her students. She shares: “Getting kids started on college pathways, whether it’s in education or their chosen career, is going to save them time, money, and help them start thinking about secondary education along with alleviating burdens I think a lot of parents feel.” Simply by offering more ways for students to understand life beyond high school, Sarah is extending an invaluable opportunity for her students to avoid missing out on secondary education as many rural students do. “There’s still a strong attitude out there that I didn’t go to college and I’m fine, so my kid doesn’t have to go,” She warns, “but they don’t realize how society has changed. You can’t run a tractor or self-propelled chopper without knowing some kind of technology. They need some additional training beyond high school. It’s not necessarily a four or two-year degree, but some extra training is essential. Through this program we’re starting early to open students’ eyes to other training that’s out there to save time and money now.”

These savings are not trivial either. Sarah reports that if students take full advantage of the college credit opportunities open to them, they can earn up to 18 credits (an entire college semester’s worth), equating to a nearly $8,000 scholarship--all this while learning early on whether or not education is the right choice for them. Sarah recalls one student who she “hadn’t realized was interested in teaching, but someone suggested they were considering it and so I got them enrolled. He then decided after going through some class observations that he wants to go into special education. As somebody who was already a role model in the school by being an athlete and a positive voice, he’s going to be such a great advocate for a vulnerable population.”

The program is still young, yet Sarah has seen some early impacts. “I would say most students at the end of the semester are more solidified and confident in becoming a teacher.” Beyond that though, Sarah has witnessed how the broader perspective on teachers has begun to turn: “Recently, people have had kind of a poor view of teachers. So when I have students telling me, ‘I want to be a teacher but my family member is discouraging me from it,' they can now say with confidence that they want to teach because of the experiences they had, and they can give people concrete ideas of why they want to pursue education.”

Further reflecting on the impact of the program so far, Sarah identifies some key pieces of advice for establishing a teaching pathway. First is to ensure the experience counts for something. Students want to feel like they are participating in something that has an impact, and that there’s something to show for it by the end, such as college credit. Second, do not be afraid to reach out to recruit for the program. Sarah tells how it took personal conversations as well as mass emails to build up enough interest to get the program going. By doing so, she was also building a regional communications network in the process. Third, ensure that school administrators are onboard. Aligning the program with the overall strategic vision of the district will not only help justify the resource expense for hosting it, but it will fuel collaboration within the district as well, opening the door for other projects down the road. Last, Sarah’s work emphasizes the importance of community collaboration for building a stronger, more resilient effort. By working together, the unique skills and assets of each of the partners come together to produce a more impactful program that builds up the capacity of the partners themselves as much as it does for the students and communities.

Building a More Inclusive Workforce in Eastern Oregon

Serving a six-county region the size of Connecticut in eastern Oregon’s high desert, Eastern Oregon University (EOU) hosts a second noteworthy education pathway program. Named the Oregon Teacher Pathway (OTP), this effort also utilizes the dual-credit model, but since its establishment in 2013 it has also maintained a specific focus on fostering cultural and linguistic responsiveness and diversity within the local teacher workforce. Tawnya Lubbes, director for both the OTP and EOU’s Center for Culturally Responsive Practices, shares that the “program is centered on culturally responsive practices, not only in professional development but also ensuring that we’re being responsive to the needs of our partners across our region. It’s centered not only on what it means to become a teacher, but really identity development through a culturally responsive lens: who are you as teachers? What are the things we need to know about teachers? What do we need to know about equity and inclusion?”

Originally, Tawnya recalls, the OTP was created to increase the number of linguistically and culturally diverse educators locally. Eastern Oregon, much like many regions across rural America, is not nearly as demographically homogeneous as the common narrative about rurality suggests. Nevertheless, the teaching workforce in the area does not fully represent the perspectives of the different communities that live there, nor fully serve the growing language diversity among the student body. The hopeful solution was to create a Grow Your Own initiative with diversity and inclusivity central to its philosophical approach.

While maintaining a core focus on linguistic and cultural diversity, the OTP itself operates much like other educator pathways. Tawnya explains that EOU will partner with local high schools in the region interested in joining OTP, and then work with them to find an educator to lead a dual-credit Introduction to Education class. After graduation, students who successfully completed the high school portion of the pathway may proceed on to EOU to complete their training through specialized classes and professional development opportunities offered only to OTP students.

Aside from attending the introductory class while in high school, OTP students are also required to participate in a weekly practicum experience in a local elementary school. This experience gives students hands-on training in the profession and quickly helps them determine if the career is a good fit. The class is a one to one pairing where the high school class visits the elementary classroom each week for an entire year. Moreover, Tawnya enthuses, “those elementary students see their peers in the upper grades who want to be teachers, so they too start seeing the value of becoming a teacher.” Even more than that, Tawnya reports that classes with the additional help from OTP students have seen higher academic achievement as more students are able to receive individualized instruction and assistance.

A second unique experience for the high school phase of the program is a spring symposium hosted at EOU. OTP high school students conduct a literature review on a topic in the education field that interests them, and then present their findings to their OTP peers and mentors. This builds the students’ research and critical thinking skills, and it nurtures a professional learning community among the OTP participants that endures into their teaching career.

Another landmark distinction for the program comes when students progress on to college. Along with receiving credit for completing college coursework during high school, OTP students who specifically choose to pursue their continuing education at EOU are offered tuition remission. Tawnya points out that “it’s really important to us that this is a remission, not a scholarship, as this way it doesn’t count against their financial aid in any way. They can still qualify for other scholarships and make university a little bit more reachable.” Rural students historically enroll in secondary education at lower rates than their non-rural peers, despite graduating from high school at similar or higher rates. A number of factors account for this, including distance to school, social expectations, and a perceived low return on investment to name a few, but simply the high cost of traveling to and attending school ranks high. EOU’s ability to cut some of the costs of schooling outright, without diminishing the impact of additional aid, is a major benefit to increase not just rural student college-going rates, but the number of aspiring teachers as well.

A final distinctive attribute to the program are the activities and structure OTP students receive while at EOU. All OTP students participate in a specially-designed mentor program, which includes a book study and peer mentors. Mirroring the students, EOU faculty also embark on a group book study, culminating in a professional development series that feeds back into the mentor program. Students are also able to maintain their ties to home by returning to their high school classes frequently, now as peer mentors and teaching assistants.

In its decade-long run thus far, Tawnya reports that 36 high school students and 39 university students are currently enrolled in the program, nearly double the 37 total alumni of the OTP since its inception in 2013. Moreover, nearly 40% of the current students represent some form of cultural or linguistic diversity. Additionally, of the 37 alumni, 33 are currently teaching and 31 of those are teaching in the region from where they graduated high school.

While the program is still growing, Tawnya is proud of the deep commitment the OTP students already share for the teaching profession. She notes that even in their first year of college, “these candidates are pretty well prepared and surpassed their peers.” Even in high school, she continues, “a hidden impact of this program is that at the high schools we see that kids in the program are consistently showing up for class.”

In organizing a new partner school to join the pathway, Tawnya shares that “the investment from the school districts is pretty minimal.” At the base level, she goes on, districts simply need to provide a teacher excited about education with a master’s degree, and that they provide transportation for OTP events and help recruit to the program. Beyond that, Tawnya believes the toughest part of the process may be having conversations with students about the importance of education and battling the many negative perceptions of the field. But for those that grow past the early fears, Tawnya tells how some students have shared back that “now that I’m a teacher, I have all this professional background to bring to the classroom and I know how to relate to my students in a different way and build those relationships.” Tawnya continues: “And we’re hearing that from the school districts too, that they want to hire EOU students because they know they’re prepared.”

Summarizing the progress of the program over the past decade, Tawnya offers a few pieces of advice to consider in starting these types of initiatives. First, “it’s a strategic investment that you’re not necessarily going to see immediate results from, but in the long term you will,” she reassures. The need for educators is both strong and immediate, and although emergency innovation and creativity may be required to fill gaps in the short term, the consistent investment into teacher pathways will pay dividends. Second, Tawnya emphasizes the power of collaboration: “We were mentored by another program when we started, and it was a great starting point, but there is no ‘golden ticket.’ People want something easy and to just do the exact same thing, but we even know from teaching that doing the exact same lesson with different groups of kids doesn’t work. You have to collaborate with your partners and be flexible to address the needs of your area.” Last, she encourages others to consider student mentorship and support for young teachers early in the process. “For us that was an afterthought in the beginning,” she admits, “But then the districts were asking who these new teachers that we sent them are. The new teachers weren’t even from the community, and they didn’t know anyone. Social recognition is huge in a rural area, so for us that mentorship and ongoing support, responsiveness to the communities, became a huge part as well.”

Aligning Good Work in the Alabama Black Belt

Rooted in the fertile soil of west central Alabama, the University of West Alabama (UWA) has long trained educators for the many rural communities that decorate the Black Belt region. More recently, through intentional collaboration and an ongoing commitment to rural service, UWA has emerged as a national leader in innovative rural programming, including the Teacher Cadet pathway. Susan Hester, coordinator for the Black Belt Teacher Corps and the Teacher Cadet program at UWA, recalls that the inspiration for the pathways initiative began much the same way: “Dr. Jan Miller [UWA College of Education Dean] and I began to speak with different superintendents of nearby districts,” she shares, “and we agreed that it would be great to start having a conveyance of students coming to campus already committed to being an education major. The idea came to us that we could begin to partner with our regional

college and career technical centers offering an education track for high school students.”

In recent years, the State of Alabama has sustained a heavy push for career and technical education (CTE). Susan tells how it was a governor’s initiative that “every citizen in Alabama graduates high school with training in a career path that can provide them with a good living. That’s the ultimate goal of education.” As part of the push, districts across the state have organized CTE centers. Susan continues: “The districts that do have a CTE center can choose paths they want their students to follow. Some choose engineering, auto repair, or medicine. And then of course there’s an education track. They make these choices based on what works in their community, what jobs are hiring, and what teachers they have specialized in those areas.”

While traditional trades, like medicine and automotive, were among the earliest pathways offered, a number of centers had elected to include education pathways. However, these early education tracks were not always connected with local higher education institutions, like UWA, to enable aspiring educators to seamlessly continue on their academic journey. Susan and her colleagues questioned why these natural connections had not been made earlier: “It just makes sense. If you’re taking the same content standards in your career tech program, then why not match it to our entry level education course and have it count as a dual credit? So then when you come to UWA, you have some hours on your transcript and a path to follow for your career.”

Hoping to test the concept, Susan and UWA partnered first with nearby Pickens County schools: “Not every career tech center would have an education path, but our partners in Pickens County do. Through their center, they had students enroll in the education pathway. We then correlated some of the courses at UWA that fit the standards and objectives of the center’s teaching.” Moreover, Susan and her colleagues decided early on that the pathway had to include hands-on practice: “They go to schools and serve as assistants to the teacher, so it gives them a leg up to be able to work on their classroom discipline, planning, and all the things you’d expect from a teacher.” Though simple in concept, the idea worked. Students and the district saw the immediate benefits of linking these different pieces of the educator pathway together. Susan remarks that “in general, every Teacher Cadet that’s come and been with us has continued and graduated.”

The basic concept at the high school level has remained the same since, but UWA has done much to build up the program once students start college. In addition to the dual credit hours, Susan explains that “once they graduate from high school and come to campus, I have what I call a Teacher Cadet Scholarship for those students who completed their career tech courses. I will give them a $1,000 scholarship each semester until they reach junior status. Then, they can switch over the Black Belt Teacher Corps and apply for a new scholarship worth $2,500 a semester.” As with the other programs explored earlier, this financial and academic assistance is crucial for rural students generally, but especially for aspiring rural teachers. These funds offset the costs incurred by rural students to travel to and attend school. The credit hours earned while still in high school accelerate their program, ensuring that they spend less time acquiring the training they desire. Then, once at UWA, students that continue into the Black Belt Teacher Corps are opened to highly specialized professional development attuned to the specific needs of rural communities. By the end of their time at UWA, new teachers are less indebted and more prepared to serve in a rural place.

This entire opportunity holds a special significance for Susan, who herself was once a classroom teacher: “In the end, we want to make sure everyone can just have a good job, support themselves, have a family if they choose to, and live a productive life. When I walked into my classroom on the first day, I was so ill-prepared. None of what I experienced was discussed in teacher education. We very much learned theory and then some degrees of practice. So, I’ve loved watching the change in the profession from when I first came to UWA. I just think, ‘Gosh, how different it is now!’ I think that’s a really good thing. We feel confident that we’re producing teachers that can hit the ground running on the first day of school. That’s the goal.”

Outcomes aside, the day-to-day logistics of the program are a testament to the power of true collaboration among different community partners. Susan explains that UWA implements memoranda of understanding with local CTE centers to begin building the full teacher pathway: “I set up the MOU and then we go visit with students. Then we’ll meet with the classroom teacher, share the syllabus for the dual credit course, and help them match up their standards to ours. It really then becomes a partnership on the academic side with the school and with the CTE center on the money and planning side.”

By the end of the planning and coordinating process, Teacher Cadets are presented with an incredibly rigorous program. “By senior year, they have so many activities going on,” Susan shares, “Every one of them is assigned to a school that they have to work in three out of five days of the week, having hands-on experiences with the teacher and students. The other two days of the week, they’re learning how to plan a lesson, what student engagement looks like, and all the standards that would be in the college course.” Again, similar to the other programs above, this high degree of rigor is inspiring high school students to go above and beyond in their work as they see the practical and immediate impact of their labor. Susan elaborates, “Those high school students really do a great job in the classroom. They’re prepared, they know what to do, and I know the teacher appreciates having them as an extra set of hands to help. Some of them even do small group instruction.” Even more, younger and older students alike are given an opportunity to see the value and power of being an educator: “One CTE teacher assigns her students to middle and upper elementary school classes to present to students about what is great about a career in education, and they can really speak from their own background about it. It works so well because when a little kid in elementary school sees the football team come to your classroom to talk about being a teacher, it’s a big deal.”

Rural Teacher Pathway Reflections

High-quality, passionate educators and well-resourced, resilient schools determine the social and economic tides of an entire community. Yet our rural schools remain dangerously understaffed and under-resourced. Meaningful, systemic solutions to the intricate web of problems leading to this issue will take time, careful consideration, and intentional collaboration. Nevertheless, there is great hope for the future state of rural education in the growing numbers of innovative approaches being taken to inspire, train, and sustain rurally-committed educators. Programs such as the three pathway initiatives explored here are extending opportunities for younger students to join the profession.

These three efforts offer key insights that can inform the creation of new pathways and the further enrichment of existing programs:

There is no one-size-fits-all: Models can vary greatly but should be chosen based on local need, attributes, and capacities. The programs discussed here were all dual-credit approaches, but as part of their larger initiative, these three pathways also incorporated club-style approaches and apprenticeship models. These additional models provide different experiences to pathway students and make the education field more accessible to all.

Aim for holistic student success: A core goal for a pathway effort should not simply be to recruit more teachers, but also to help rural students achieve post-secondary success. These efforts often made going to college more feasible through earning college credits, discounting the cost of schooling, and exposing students to life in college. Incorporating these elements into a pathway effort can improve recruitment.

Foster self-awareness as much as self-actualization: While these programs explicitly seek to recruit and train future generations of rural teachers, they also serve to help participants explore their identities more broadly. A lack of self-understanding can ultimately undermine an educator’s long-term sustainability if they discover later that their chosen career does not fulfill their interests and needs. These early pathways have an incredible opportunity to foster a student’s sense of self, which will serve them across their entire life as well as in the classroom.

Seek collaboration: Working together with local partners to pool ideas and resources will create a more rigorous and resilient program. The power of true collaboration cannot be overstated. Many of the pieces needed to create strong educator pathways already exist, and so the task at hand is to bring people to the table to figure out how to assemble the puzzle. Working together carries the additional benefit of creating stronger bonds within the community as well.

Be patient and persistent: Building these efforts and seeing their impact may take time. The cumulative effect of continued investment into the future success of students will be seen in the growing strength of the local teacher workforce. However, there are some immediate impacts if pathway students are able to participate in hands-on experiences. In those cases, not only are practicing teachers more supported, but their students exhibit higher degrees of academic achievement from the extra assistance. Moreover, the pathways participants find themselves more confident to truthfully share positive narratives about the education sector and rural places.

These early education pathway efforts are gaining traction nationally, but more should be done to ensure their success. Thankfully, there’s still great ways to support the continued growth of these initiatives, including:

Forging partnerships: Even for those programs already built on a solid foundation of local collaboration, new partners bring new insights and life to programs. Finding ways to support your local schools or colleges to build these pathway programs will be a service to not only the students and schools, but to the whole community by extent.

Changing the narrative: As some of these examples shared, there is a pervasive narrative undermining the prestige and value of the education profession. Schools need passionate teachers, and communities need strong schools. Perpetuating a negative narrative about the worth or commitment of educators ultimately leads to the social and economic decay of a place. Sharing stories of exemplary teachers, showing the impact of educators locally, and nurturing the interest of students in becoming an educator are all small but meaningful steps toward creating a constructive narrative about education that can inspire more to join the field.

Funding proven models for success: Investing in the success of future rural teachers is investing in the prosperity and vitality of rural communities. A rural educator is not only empowering the next generations of local citizens, but they are community leaders and role models as well. The impact of even a single, inspired and supported rural teacher-leader extends from student success in the classroom to stronger, more prosperous, and more harmonious community relationships and organizations.

Rural Schools Collaborative believes that building a sustainable future for rural communities must come through the intersection of place, teachers, and philanthropy. Educator pathway programs exemplify the realization of this vision by uniting the collective good will of teacher preparation experts, community members, and aspiring teachers in service of strong schools and vibrant communities. Rural Schools Collaborative works with regional partners in over 30 states to advance this vision of rural possibility, including the three programs surveyed here. I invite you to do the same by either connecting with Rural Schools Collaborative and its Regional Hub Partners, or by reaching out in your community to get a good idea started. By working together for the advancement of good ideas, rural prosperity is not only possible, but achievable.

Thank you to Sarah, Tawnya, and Susan for sharing their perspectives, and to RSC’s Regional Hub partners at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, Eastern Oregon University, and the University of West Alabama for sharing about three incredible efforts, and for all they do to further local rural educator pathways.

And, a final thanks to John Glasgow (Illinois) for authoring this article!