Editors Note: Renee Carr is the current chief financial officer for Arkansas’ Rural Community Alliance, its former executive director, and a member of the Rural Schools Collaborative board of directors. She is also a history buff with a keen sense of family and place. Renee recently sent us this wonderful essay, which connects rural people, regions, and place-based education. America’s rural landscape is a portrait of diversity, but Renee reminds us of our shared heritage--agriculture, hard work and public education.

By Renee Carr

When I met fellow Rural Schools Collaborative board member Josh Gibb, I was intrigued by his enthusiasm, vision and successful direction of the Galesburg Community Foundation. I have never been to Galesburg, Illinois but wanted to know something about this place and feel a connection to it, just based on Josh’s enthusiasm. I live in the hills of north Arkansas in a small community called Fox. A few weeks ago I found my connection to Galesburg, but it goes way back to 1930, long before Josh and I were around to champion rural schools and communities. Our connection goes back to a time when our great grandparents worked hard every single day to provide for their families in rural places.

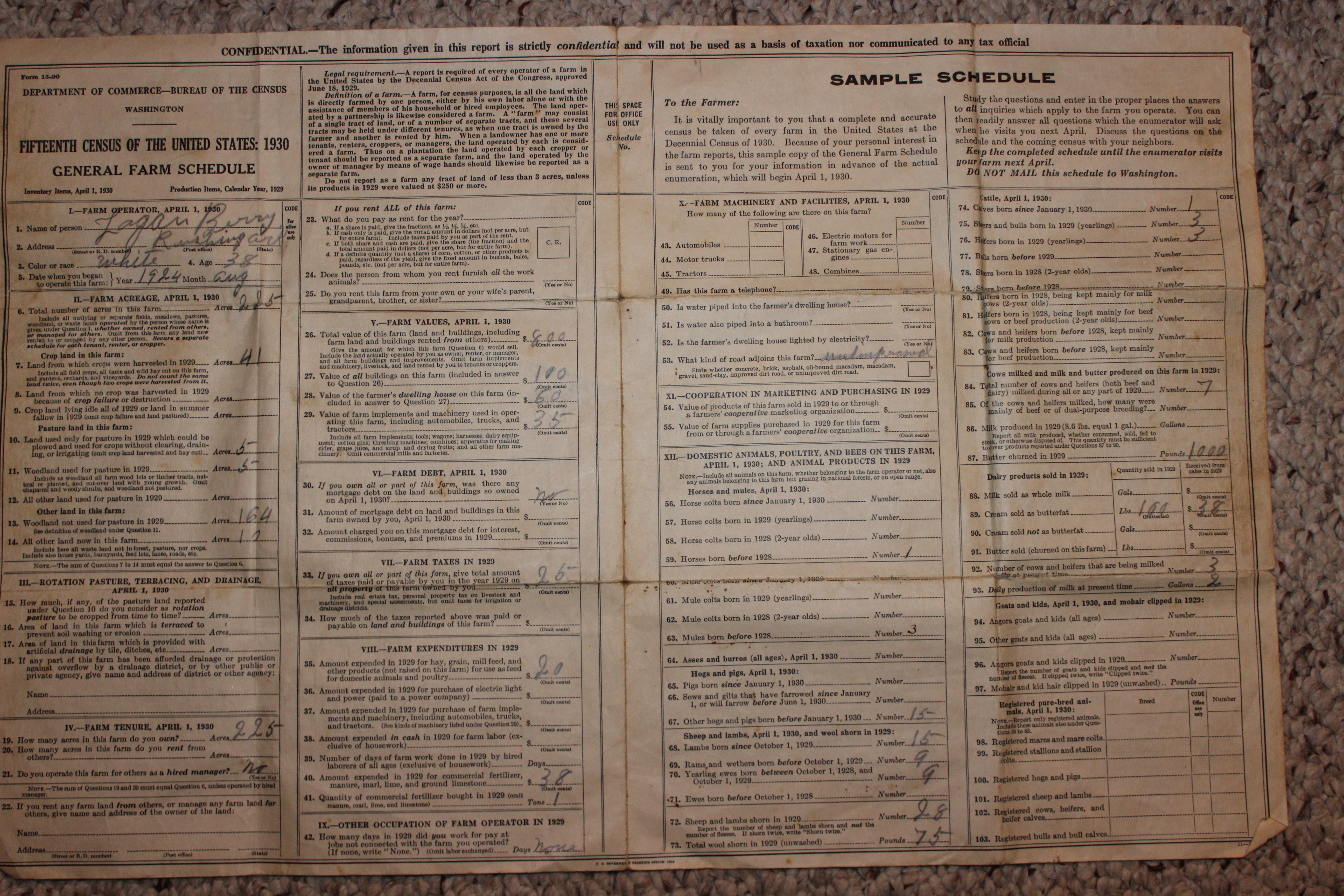

My 96 year-old Grandmother died last year and her eleven children have been going through the memorabilia and items she left behind. One of my mother’s sisters brought a box of old documents to my mother and told her, “I know you’ll know what to do with these.” Being a local history buff and a genealogist in my spare time, I couldn’t resist looking through the large shoe box. The most exciting item was a large fold-out 1930 U.S. Census farm worksheet (pictured below) on which my great grandfather, Logan Berry, had painstakingly filled out every block including any items sold from the farm in 1929 from hogs to cows to corn. He listed seven cows. The most impressive figure to me was his entry that 1,000 pounds of cream had been sold from the farm during that year. Some more digging through the box landed some postcards with a return address of Beatrice Creamery Company, Galesburg, Illinois. Apparently the postcards (see below) were placed on the cans of cream and mailed to Galesburg. Aha, my connection to Josh and his Illinois community!

from the farm during that year. Some more digging through the box landed some postcards with a return address of Beatrice Creamery Company, Galesburg, Illinois. Apparently the postcards (see below) were placed on the cans of cream and mailed to Galesburg. Aha, my connection to Josh and his Illinois community!

Interestingly, my Grandfather also preached and had written scripture citations and some of his sermon themes on the back of these cards, and that was likely why the postcards had been kept over the years.

A few days later I was at my mother’s house and she unearthed a story she had written about her grandmother making cream—the same cream that had made its way to Galesburg decades ago. My mother, Angalee Rushing, is a retired school teacher from Rural Special School. She taught sixth grade and encouraged her students to write. The students did interviews with family and community members and wrote their stories. While they wrote in class, my mother also wrote. The story shared below about her grandparents Logan and Goldie Berry, she titled “Did the Cream Check Come Today?” The Great Depression was only beginning when my great grandfather filled out his farm census in 1930. But as most rural folks will tell you, hard economic times take a while to hit rural communities, but they stay around much longer. My mother was born in 1938, so her memories are from the 1940’s and early 1950’s.

So thank you Galesburg, Illinois for providing a means for my large family in the north Arkansas hills to survive in those difficult economic times. And maybe in some small way my great grandparents also contributed to Galesburg.

Did the Cream Check Come Today, by Angalee Rushing, April 22, 1987

I can still remember the smell of my grandparents’ separator house. It was neither a bad smell nor a good smell but simply a unique smell.

My first clue as to what was going to happen was when my Grandpa would interrupt our play to say to my aunt, “Marie, it’s time to go get the cows.”

Then we would begin an enjoyable hike (for me). But to my aunt {only two years older than me} it was simply a boring chore that had to be done daily.

My grandparents lived on Turkey Creek. So we leisurely started our hike through the pasture along the creek, looking at the wild flowers and butterflies; hearing the chirping of the birds and the squeaking of the insects; smelling the freshness of growing things but mostly just talking and thinking our worry-free thoughts. My aunt would stop intermittently to call, “So-o-o-k, Bossy.” Because if she could get the lead cow to make her start toward the barn the other cows would follow and she wouldn’t have quite so far to walk.

Once the cows had started their trek to the barn, there was little we had to do except maybe to remind one that had spied a green juicy morsel growing along the way, to keep moving.

After the cows were gathered in the lot beside the barn, the milking process began. Each cow knew exactly which stall to go into and stood patiently trying to retain her dignity as the pulling and squeezing process began, only occasionally flicking her tail at a persistent fly or stamping her foot because one insisted on biting her ankles. Then the milker might stop and quietly annihilate her persecutor, then continue on with the pillage of the raw product.

I can still remember the sound of those steady streams of milk tinkling against the tin bottom of the empty bucket and slowly the change to a muffled thud as the bucket began to fill with milk.

As each cow was milked and “stripped” the milk was dumped into a larger pail sitting high on a shelf out of reach of an errant hoof. When two of those large pails were full, Grandma would carry them to the separator house. Then my attention was diverted from the barn.

The big black separator was a mystery to me. Oh, how I loved to watch and study the mystery as it began to unfold. First, Grandma had a big white cloth which she put over the bucket and poured the milk through. The milk appeared as pearls on the cloth and then began pouring out like a waterfall. The milk was strained into a big silver bowl which sat atop the big black machine. When the bowl was full, the hard cranking and turning of the handle began. At first the handle turned slowly with a hard resistant groan then it became easier as centrifugal force began to work for Grandma with a hum and a purr. This was quite a visual effect on my senses that have stayed with me through the years. Within the old brownish, unpainted, aged wood walls sat the big black machine with the large silver bowl on top draped with a snowy white cloth. Beside the black machine were the tin cream cans. Then there was Grandma enwrapped in her oversized, starched, white apron with her delicate embroidery work on the bib and pocket. As she turned the crank slowly the white milk began slowly to flow from one spout and then became faster until it was a steady flowing stream of “blue john” (milk without cream) pouring out one spout. Much slower in starting and slower in flowing was the cream from the other spout. The color was also a richer creamier color.

The old “blue john” was quite worthless after the cream was taken out. The family didn’t consume this milk. However, Grandpa would mix “shorts” (particles left when wheat is ground into flour) with the de-creamed milk and feed it to the hogs.

Grandma, after finishing separating the milk then still had the task of washing up the separator with its seemingly millions of discs, the milk buckets, cream cans, strainer cloth, work table, and even the floor. This was perhaps the worst part of the whole process.

Water was a precious, hard to attain commodity. The well was located nearby. However, the water had to be drawn from the well, toted inside the separator house, heated, and then everything washed, scrubbed, and sterilized.

The cream was stored in the cream cans without refrigeration until time for the weekly trip to the train depot in Shirley. Our destination was the old platform by the tracks where the cream cans were unloaded. The full cans were replaced with empty cans to be taken home and filled with cream again. Sometimes, the mailman would pick up the full cream cans and bring back empty cans.

Today cream cans are only used for decorative purposes, but when I see a mailbox sitting on a cream can or a beautifully painted cream can I’m reminded of the sights, sounds, smell, and hard work involved in separating the milk.

I’m sure I felt that the whole process of separating the cream from the milk was just a fun thing and taking off the cream was just an excuse to see the train come puffing into the depot and hear the whistle echoing through the river valley. Or I may have thought all of the hard work was just so we could have that yummy, thick, luscious cream on hot chocolate gravy with Grandma’s hot, giant-sized biscuits. On second thought, the vision of the thick cream melting on the rich brown chocolate reminds me that maybe it was worth all the tedious, grueling work involved in producing the cream. And if that wasn’t enough to justify the hard work surely the thick cream on Grandma’s steaming huckleberry cobblers would do the trick.

But I know that the real purpose behind all the hard work was for the money acquired in the sale of the cream. This was probably the main income for my grandparents, and though Grandma had her “egg money” for the little extra’s like her crochet thread of which she made such beautiful scarves, handkerchiefs, laces and even tablecloths and bedspreads as she sat in her chair in the lamplight with the crochet hook playing hide and seek in the thread. The real necessities were bought with the money from the sale of the cream. This was the “cream of life.”

I can now empathize with the feelings that they must have felt as one would ask, “Did the cream check come today?”

Renee Carr lives in Fox, Arkansas. When she isn't working hard for Arkansas' small towns and rural schools, Renee helps lead Rural Educational Heritage, Inc., a nonprofit organization.

To learn more about the value of place-based education, click here.